Chapter 5 Regulation & Standards

5.1 Intro Regulation

We will start by understanding how policy and legal documents evolved until today.

Then we will introduce to some basic concepts of different legal documents and how they related to each other, so as its dependencies.

We will move on to scope, or answering the question “what are these documents trying to achieved?” How they related to connected areas, as building codes, environment and urban planning.

Afterwards we will introduce the main legal documents, or the cornerstones of most national regulations and lastly, how they related and set the tone for national frameworks.

Looking to the evolution and overall History, or how it evolved to its current shape.

We can trace from the 50´s.

5.1.1 Trends and international agreements

In the 70´s the evidence and acknowledgment of the externalities and impact, namely of the use of fossil fuels and other specially pollutant industries starts , where the recognition of the environment as a good in its own right (sometimes referred as the Third generation rights) but, nevertheless one that was always be vulnerable to tradeoffs against other similarly privileged but competing objectives, including the right to economic development.

Consensus begins to form in the 1980´s and in 1988 the WMO established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change with the support of the UNEP.

The Kyoto protocol was the first agreement between nations to mandate country-by-country reductions in greenhouse-gas emissions. Kyoto emerged from the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which was signed by nearly all nations at the 1992. The framework pledges to stabilize greenhouse-gas concentrations “at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”. That treaty was finalized in Kyoto, Japan, in 1997, and it went into force in 2005.

As a replacement of the Kyoto Protocol, in December 2015, 195 countries adopted the first-ever universal, legally binding global climate deal. known as the Paris Agreement.

The agreement sets out a global action plan to put the world on track to avoid dangerous climate change by limiting global warming to well below 2°C.

Along with that the UN set The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the successor to the Millennium Development Goals). Out of the 17 SGD´s, 4 related to this course:

Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

Goal 13: Climate Action

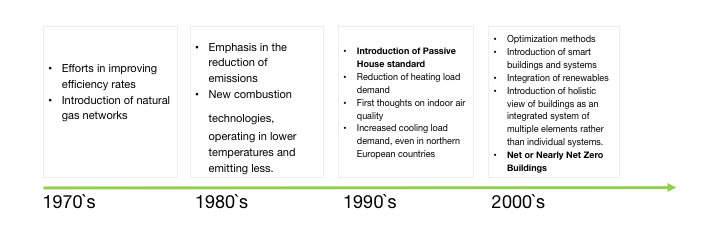

Looking at the overall History of Energy Efficiency in Buildings

Looking at the Scope and Background of EU, The main goals are the freedom of movement of goods, persons, services and capital.

The early measures up to the end of the 1970s, and then describes three main steps: the internal market; the climate change package; and the first steps towards security of supply framework.

So went from trade agreement to common Energy Policy, or

From

European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), administrative agency established by a treaty ratified in 1952, designed to integrate the coal and steel industries in western Europe. The original members of the ECSC were France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. The organization subsequently expanded to include all members of the European Economic Community (later renamed the European Community) and the European Union. When the treaty expired in 2002, the ECSC was dissolved.

To

Energy Union

The Energy Union Strategy is a project of the European Commission to coordinate the transformation of European energy supply. It was launched in February 2015, with the aim of providing secure, sustainable, competitive, affordable energy.

The European Council concluded on 19 March 2015 that the EU is committed to building an Energy Union with a forward-looking climate policy on the basis of the Commission’s framework strategy, with five priority dimensions:

Energy security, solidarity and trust

A fully integrated European energy market

Energy efficiency contributing to moderation of demand

Decarbonising the economy

Research, innovation and competitiveness.

The strategy includes a minimum 10% electricity interconnection target for all member states by 2020, which the Commission hopes will put downward pressure onto energy prices, reduce the need to build new power plants, reduce the risk of black-outs or other forms of electrical grid instability, improve the reliability of renewable energy supply, and encourage market integration.

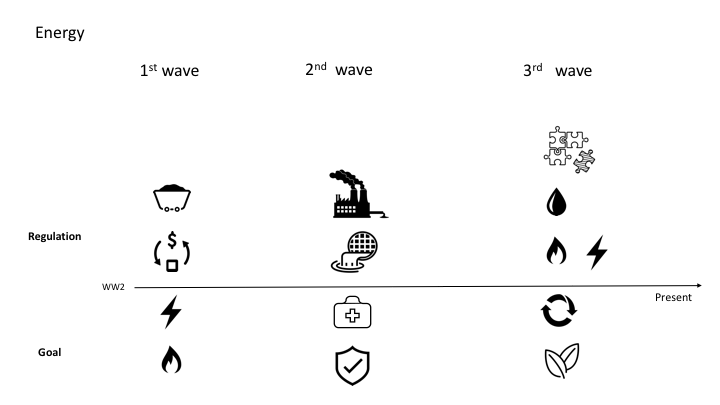

We can spilt 3 main waves, which reflect concerns and events of that time, so as overall incremental regulation, moving from basic needs, as supply and trade, to negative externalities, to full integration of economic and sustainable goals.

In the same way regulation of basic human implementation was achieved, new layers and goads were pursuit.

1st Wave, where the goal was access to goods, namely coal, so we can trace back to the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), where regulation was related to trade and tariffs.

Council Directive 90/531/EEC of 17 September 1990 on the procurement procedures of entities operating in the water, energy, transport and telecommunications sectors

Directive 94/22/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 1994 on the conditions for granting and using authorizations for the prospection, exploration and production of hydrocarbons

Directive 2013/30/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 June 2013 on safety of offshore oil and gas operations and amending Directive 2004/35/EC

The Oil Stocks Directive (Council Directive 2009/119/EC ) of 14 September 2009 imposing an obligation on Member States to maintain minimum stocks of crude oil and/or petroleum products.

Directive 2003/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2003 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity

2nd Wave, where the goal was to improve and guarantee common safety and health standards. The Regulation of most industries, namely its externalities, as emissions and waste.

As for example:

Solutions to prevent and minimize environmental damages are a requirement to companies of a large number of industries that want to have licenses to operate in the market. Currently, the following main pieces of legislation applicable in this field

The IPPC Directive (Integrated Pollution Prevention & Control), that establish the politics on prevention of pollution;

Several sectorial directives, which lay down specific minimum requirements, including emission limit values for certain industrial activities (large combustion plants, waste incineration, activities using organic solvent and titanium dioxide production).

The Directive on industrial emissions 2010/75/EU (IED) that has entered into force on 6January 2011 and has to be transposed into national legislation by Member States by 7January 2013.

EU European Trading Scheme (ETS) Policy, launched in 2005, works on the “cap and trade”principle. The number of allowances is reduced over time so that total emissions fall.

Directive 2009/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 amending Directive 2003/87/EC so as to improve and extend the greenhouse gas emission allowance trading scheme of the Community (Text with EEA relevance)

Directive 2009/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the geological storage of carbon dioxide and amending Council Directive 85/337/EEC, European Parliament and Council Directives 2000/60/EC, 2001/80/EC, 2004/35/EC, 2006/12/EC, 2008/1/EC and Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006

3rd wave, with the aim of setting a decarbonized economy, so as an efficient and sustainable use of resources, where Regulation falls into energy markets, as electricity, gas, so as the integration of a single EU Energy Market.

Directive 2009/28/EC on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources (RES)

Directive 2012/27/EC on energy efficiency

Directive 2009/72/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and repealing Directive 2003/54/EC

And finally the Winter Package:

Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/1222 establishing a guideline on capacity allocation and congestion management

Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/1719 establishing a guideline on forward capacity allocation

Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/1447 establishing a network code on requirements for grid connection of high-voltage direct current system and direct current-connected power park modules

Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/631 establishing a network code on requirements for grid connection of generators

Regulation on laying down guidelines relating to the inter-transmission system operator compensation mechanism and a common regulatory approach to transmission charging (838/2010/EU)

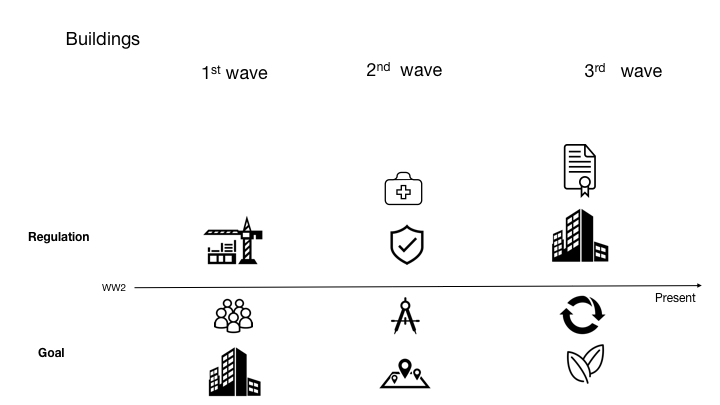

On Urban Planning and Buildings we can state:

1st wave, namely after the war to reallocate, reconstruct cities and provide housing at affordable prices, so regulation was towards construction, access (housing) and property rights.

2nd wave, with the goals to set overall urban planning and assume basic standards of safety, hygiene and public health, regulation was in setting minimum standards of the last 3 goals.

3rd wave, promoting sustainable cities and communities, regulation for buildings, use of resources and setting standards, as the Energy Certification in Buildings for these assets be traded and used.

Unlike in Energy, regulation from EU regarding Buildings, only emerges in this 3rd wave, where the first two were typical competences of local governments.

5.1.2 European and National Legal Frameworks - Types of Regulatory mechanisms

The aims set out in the EU treaties are achieved by several types of legal act. Some are binding, others are not. Some apply to all EU countries, others to just a few.

The legal basis for the enactment of directives is Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (formerly Article 249 TEC), under section 1 “THE LEGAL ACTS OF THE UNION”

According to Article 288:

To exercise the Union’s competences, the institutions shall adopt regulations, directives, decisions, recommendations and opinions.

A regulation shall have general application. It shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States.

A directive shall be binding, as to the result to be achieved, upon each Member State to which it is addressed, but shall leave to the national authorities the choice of form and methods.

A decision shall be binding in its entirety. A decision which specifies those to whom it is addressed shall be binding only on them.

Recommendations and opinions shall have no binding force.

Types of EU legal acts:

Directive;

Regulation,

Decision;

Recommendation

Opinion

A “directive” is a legislative act that sets out a goal that all EU countries must achieve. However, it is up to the individual countries to devise their own laws on how to reach these goals. One example is the Energy Efficiency Directive.

A “regulation” is a binding legislative act. It must be applied in its entirety across the EU. For example, when the EU wanted to make sure that there are common safeguards on goods imported from outside the EU, the Council adopted a regulation.

A “decision” is binding on those to whom it is addressed (e.g. an EU country or an individual company) and is directly applicable. For example, the Commission issued a decision on the EU participating in the work of various counter-terrorism organisations. The decision related to these organisations only.

A “recommendation” is not binding. When the Commission issued a recommendation that EU countries’ law authorities improve their use of videoconferencing to help judicial services work better across borders, this did not have any legal consequences. A recommendation allows the institutions to make their views known and to suggest a line of action without imposing any legal obligation on those to whom it is addressed.

An “opinion” is an instrument that allows the institutions to make a statement in a non-binding fashion, in other words without imposing any legal obligation on those to whom it is addressed. An opinion is not binding. It can be issued by the main EU institutions (Commission, Council, Parliament), the Committee of the Regions and the European Economic and Social Committee. While laws are being made, the committees give opinions from their specific regional or economic and social viewpoint. For example, the Committee of the Regions issued an opinion on the clean air policy package for Europe.

Directives usually don´t have a direct effect.

Even though directives were not originally thought to be binding before they were implemented by member states, the European Court of Justice developed the doctrine of direct effect where unimplemented or badly implemented directives can actually have direct legal force. Also, in Francovich v. Italy, the court found that member states could be liable to pay damages to individuals and companies who had been adversely affected by the non-implementation of a directive.

5.1.3 “Soft Law”

Lack of features (vs “hard law” such as:

obligation,

uniformity,

justiciability,

sanctions,

and/or an enforcement staff

In the discussion of new governance in the European Union, the concept of “soft law” is often used to describe governance arrangements that operate in place of, or along with, the “hard law” that arises from treaties, regulations, and the Community Method. These new governance methods may bear some similarities to hard law. But because they lack features such as obligation, uniformity, justiciability, sanctions, and/or an enforcement staff, they are classified as “soft law” and contrasted, sometimes positively, sometimes negatively, with hard law as instruments for European integration.

“Soft law” is a very general term, and has been used to refer to a variety of processes. The only common thread among these processes is that while all have normative content they are not formally binding.

In his definition, Snyder describes soft law as “rules of conduct which in principle have no legally binding force but which nevertheless may have practical effects.” In recent years there has been an increase in interest in soft law in the EU.

There are several examples of “Soft Law”:

Industry standards (as ISO´s, ..);

Market costumes and practices;

Recommendations and opinions;

They may have asimilar strength of hard law, still are not enforceable. For example the “Best Available Techniques (BAT´s), like stated in Industrial Emissions Directive and IPPC Directive, concerning mitigation and prevention mechanics.

5.1.4 Scope and Articulation between EU, National Frameworks and International Standards

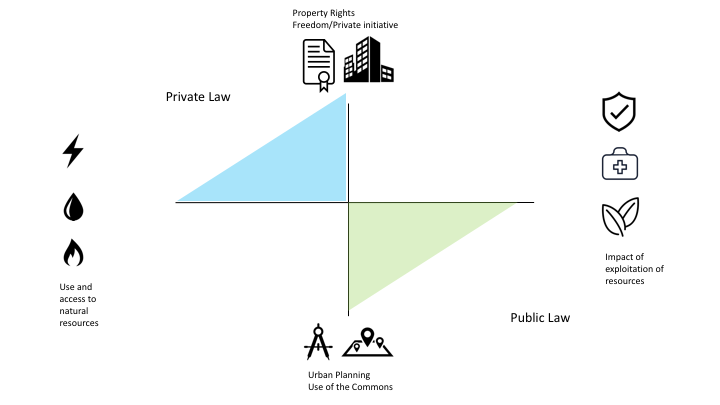

The use of the commons and property rights (Coase) it´s a well studied case of where externalities, such as pollution, if not internalized, individuals will have an incentive to over exploit (commons), so several schemes try to internalize such externalities or mitigate public interest with private interest, by setting trade offs.

When analyzing the legal system, using the classical distinction between:

Private Law - applies to relationships between individuals (and companies) in a legal system (e.g. Contract Law)

Public law applies to the relationship between an individual (and Companies) and the Government. (e.g., Administrative Law)

We can see conflicting areas

- Energy and Environmental;

- Property Rights (Real Estate) and Urban Planning;

For example:

Property rights are delimited by Administrative Law provisions (when you need a permit to construct) or when environmental provisions cap use and access to natural resources (for example, when is required Environmental Impact Study, for starting operating large combustions plants, or by limiting the type and capacity of energy generation for self-consumption.

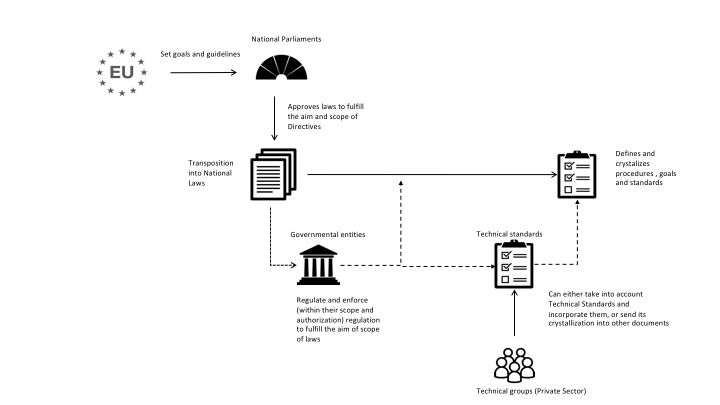

To close, it is important to understand how each document relates to each other. Or how Directives, National Regulation and other reference documents interconnect with each other.

We already know that Directives, in principle, do not have a direct effect and Member States have to fulfill internally those guidelines.

Directives are approved, and Member States have a certain period to transpose these Directives into national Law. Usually there is some freedom for adaptation, because each country has its own realities and system. EU states a goal, MS have to, internally, with their own legal tools, produce the mechanics to fulfill these goals.

Parliaments, can either decide to incorporate all definitions and procedures into a single piece of legislation or, attribute competence and authorization to a certain governmental entity, for fulfilling the details. A typical case is regulations to fulfill a certain piece of legislation. These entities are also mandated to execute, regulate, de application of such regulations.

Technical standards, they can either be incorporated into legislation and regulations or, a certain law or legislation sends the interpretation to these technical standards produced by industry or professional peers. So these documents even not having originate features of hard law, they end having similar strength due to being used by enforceable legal pieces of legislation or regulation.

A typical example would be:

EU set a Directive to improve EE, Parliament transpose Directive into national law and mandates a regulatory agency to execute the attributions within this law. The regulatory agency, writes a regulation that uses as standards an international standard to define what EE means and how its measure.

5.1.5 EU regulation

5.1.5.1 EU Directives

Energy Performance in Buildings Directive (2002/91/EC,2006/32/EC, 2010/31/EU)

Energy Efficiency (2012/27/EU)

Renewables Energy Directive (2009/21/EU)